It breaks my heart when I hear elementary teachers shamefully tell me that they were “never good at math”, hated math or just don’t feel confident. The truth is, if this is you, it is a GIFT. If you never felt confident in math, then you know exactly how your students feel. Not only that, it will make you an anchor chart machine.

Anchor charts are the missing link between our instruction and students practicing mathematics. We as teachers may have taught a concept 5 years in a row or more, but for students it could be their first time hearing it. They also may have holes missing in previous years instruction for a variety of reasons. Giving students what they need right up on their wall is the first step in helping them make connections, remember complicated processes or learn brand new vocabulary. You have English Language Learning students? Special Education students? It doesn’t matter who is in your classroom, anchor charts are good for ALL of your students.

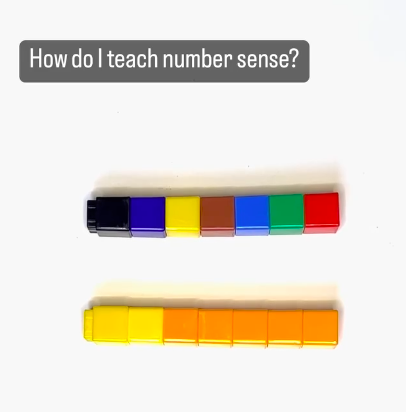

Take this anchor chart for a grade 2 unit on number lines for example:

There are things on that anchor chart that every single adult takes for granted. We know what a tick mark is, we know what a point is, and we know what to do when numbers are missing. These are things that the majority of our students have never experienced. This anchor chart is especially important because number lines come up in so many concepts for many years to come.

Anchor charts are best made when you think about the following 5 things:

- How can we make it together? This is critical. When learning is synthesized at the end of a lesson, that’s the perfect time to add to your anchor chart, and as much as possible written in student friendly language.

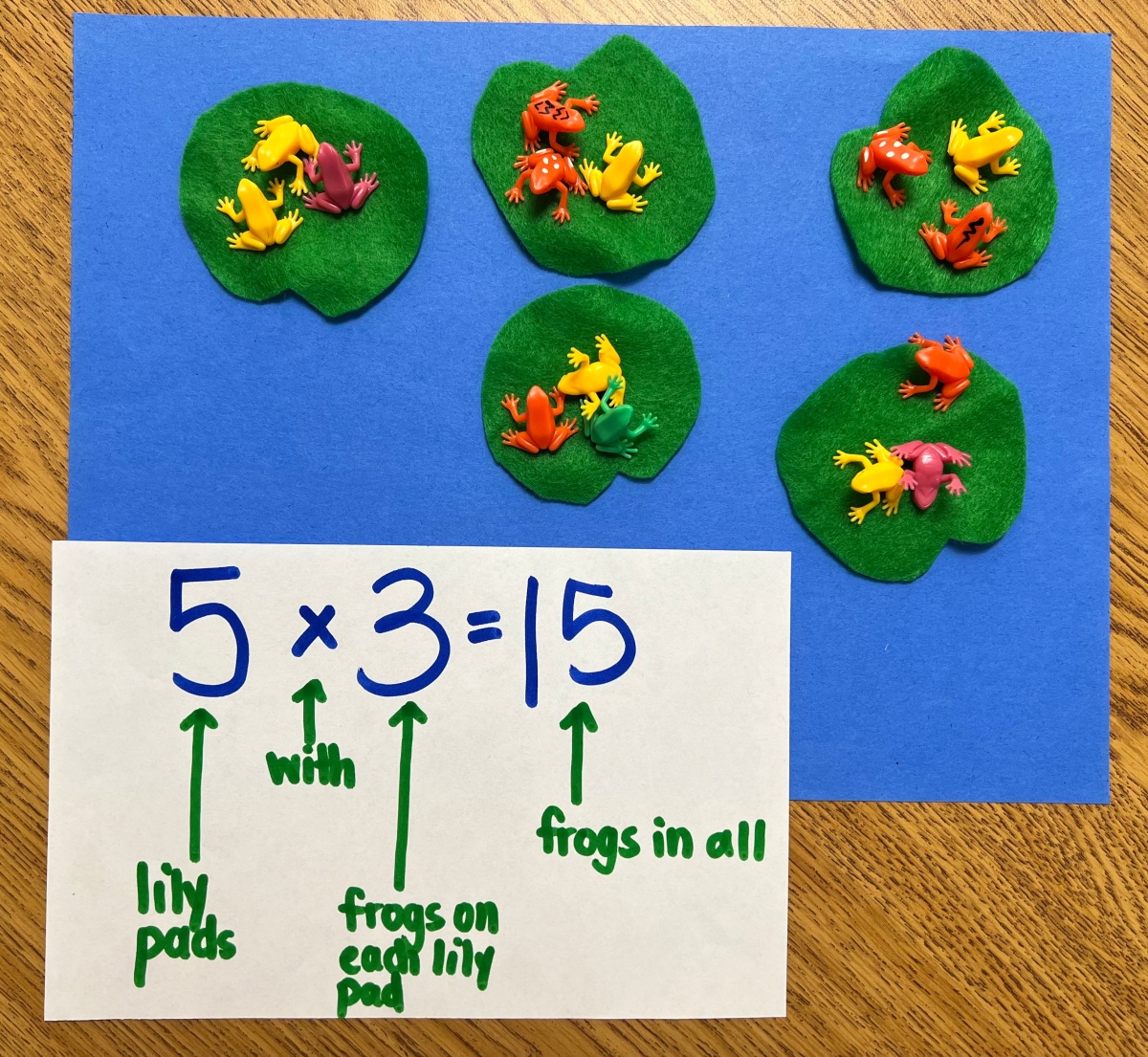

- What new math specific vocabulary needs to be explained on the chart? Act like a new learner, like you’ve never heard some of these words before. Which belong on the anchor chart? How can words be written with precision, but still student friendly? Anchor charts explain that we can use math words like point instead of dot or tick mark instead of line.

- What misconceptions do students have? What is important to remember, and what errors are you are seeing your students make in the lessons?

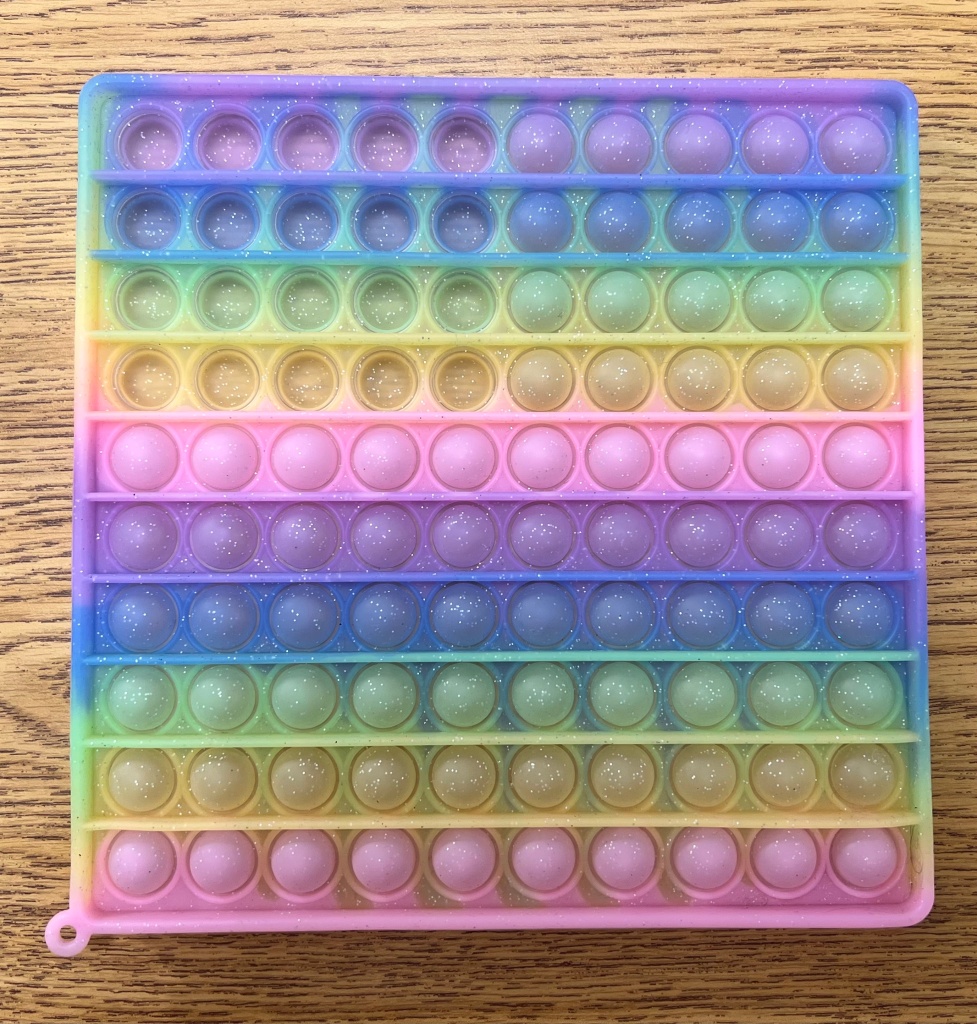

- What is the least amount of words I can put on it? Visuals are KEY. The more visuals you have the better! They are both engaging and beautiful. Some of the anchor charts I’ve seen are absolute works of art.

- How new is this material to my students? If they haven’t had prior exposure to the concept, it MOST definitely belongs on your wall.

This is not an exhaustive list, but a place to start. The more you work on anchor charts the better you will get at them. As you walk around helping, you’ll notice a lot of the same questions keep on getting asked. This is an instant signal that you need to get that up on the wall to help mass amounts of students.

I wish this is something that I would have known when I was a first year teacher, when I thought I was bad at teaching math. It would have been an incredible thing to really think through all those things that I struggled with as a student, learn along side them and provide the proper supports.